Before the Huntress: Discovering the Neolithic Ancestor of Artemis

Vidra, The Neolithic Guardian of Nature and the Wild

Perhaps Artemis Never Made it to Bucharest…

Today I’m leaving Romania and I have mixed feelings about this trip. In many ways I enjoyed meeting my cousin again (I haven’t seen her in 14yrs) and playing and getting to know my little niece, her 7yr old daughter. Romanians are famous for their hospitality and openness, and my cousin did not disappoint. Her warmth and openness allowed me to work, visit and philosophize about what life would’ve been like for me, had my parents never escaped the Communist Regime almost 40 years ago.

After sleeping off the jetlag, and sharing many coffees with the only relation I have left in my home country, I began my trek to many of the archaeological museums within a 2 hr distance from Bucharest in search of Artemis. I found a handful of Venus artifacts, one Apollo bronze statuette, and a bunch of stone Mithras representations but not one, not one!, of Artemis or Diana.

Frustrated, I resolved myself to look for pieces, or findings, that pre-dated the Romans, Dacians and Thracians. I asked myself, what might’ve been dug out of the earth of my home land that could give me a clue in finding connections to a Goddess that calls me so deeply. Was my connection with the Goddess of the wild something that developed BECAUSE I escaped Communist Romania, and as such She found me in the suburbia of Toronto, or was there an umbilical connection thousands of years deep in the soil of my birth? (Some times, when I can’t decide where I would like to build the Artemis Centre, I ask the Goddess if She wants to travel across the ocean with me to North America, or if She prefers to be resurrected in her ancient land. The lack of archaeological findings in Romania connected to Her worship make me think She travelled across the ocean already, to find me.)

With this new chronology in mind, I embarked on finding vestiges of Neolithic or Eneolithic worship, particularly of the sacred feminine. Dear reader, (insert smh emoji here) the findings were slim. So slim. The people I met who worked at the museums were extremely generous with their time and patience. They turned on lights in rooms no one really walked through, and unlocked doors to exhibits long left unexamined. We talked at length about the lack of archeological funding, publications or even interest in the Neolithic world of Romania. That is not to say there is none, the passionate guides shared links, books, even gave me postcards to take home with me, because they believe so deeply in the work that has been done, and hope for more work to be done in the future. The lack of enthusiasm seems to be political (you are not shocked, I know) and bureaucratic.

It was in Oltenati, while talking to a particularly passionate guide at an ‘officially closed’ exhibit that he mentioned the goddess Vidra. After listening to me go one at length at all the ways a Neolithic deity can connect to the Goddess of Nature and the Wild, he interrupted, “Have you seen that one piece they found of Vidra?”

I paused. “Vidra?'“ I repeated hope filling my heart.

“The goddess of water right?

They found an artifact?

Where?

When?

How?

Is she intact?” questions spilled before I could catch my breath.

“Yes,” he smiled a little, proud of himself, “They have one piece at Palatu Sutu. It is quite large and totally intact. You have to go!”

I laughed, relieved to remember the Palace was easily accessible by bus in Bucharest, and I still had one more full day left in the city.

“I’m going!” I clapped joyfully, “Tomorrow!” And I could not wait.

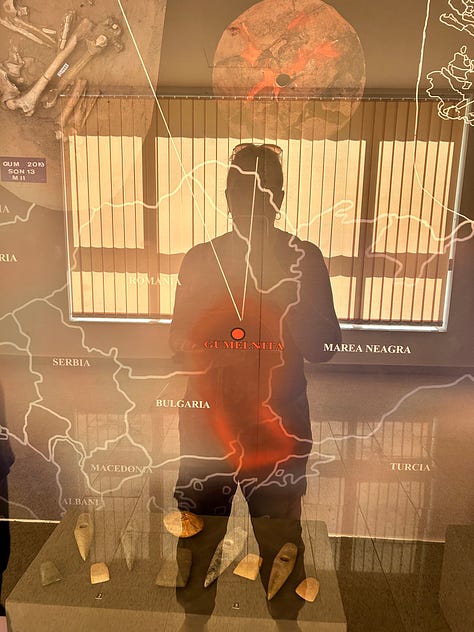

And so, I jumped on the bus the next day, researched all I could find about Vidra and her worship in English and Romanian, for the two hours it took me to get to central Bucharest, walked excitedly into Palatu Sutu, straight to the ticket office and said, “I’m here to see the goddess Vidra.” And I did.

Here is what I found:

The Forgotten Goddess Vidra and the Spiritual Legacy of the Neolithic World: A Possible Connection to Artemis

In ancient Dacian and Thracian spirituality, nature held a sacred place, with many deities connected to the elements. One such goddess, though largely forgotten in modern times, is Vidra, a deity likely tied to water and aquatic animals. Vidra’s name, derived from the Romanian word for “otter,” places her within a world where rivers, streams, and lakes were vital for both life and the spiritual health of a community.

Vidra's role as a water deity can be seen in the broader context of Dacian spirituality. Though no direct records of her worship have survived, water deities were central to the Dacians' reverence of nature. As Mircea Eliade points out in De la Zalmoxis la Genghis-Han, "Mitologia dacică, pe care o putem reconstitui doar fragmentar, a fost centrată pe divinități naturale, iar zeii râurilor și apelor joacă un rol important în cultul lor." ("Dacian mythology, which we can only reconstruct in fragments, was centered on natural deities, and the gods of rivers and waters played an important role in their worship.") Vidra would have likely represented the life-giving and purifying power of water, a resource essential for survival and agriculture.

Vidra and the Possible Connection to Artemis

One compelling hypothesis is that Vidra may have been syncretized with or influenced by the Greco-Roman goddess Artemis, particularly in her aspect as a protector of nature and animals. Artemis was a multifaceted goddess associated with the wilderness, hunting, and animals, including aquatic creatures. Her role as a guardian of the natural world and animals, especially wild animals like otters and deer, presents intriguing parallels to Vidra’s possible function as a water deity.

After the Roman conquest of Dacia, many indigenous deities were absorbed or syncretized with the gods of the Roman pantheon. Vidra, as a local water deity, could have merged with the Roman and Greek interpretation of Artemis, who also had strong associations with rivers, springs, and wild animals. Artemis’s Naiads—water nymphs who were believed to inhabit rivers and springs—could also reflect Vidra’s association with water sources.

Vidra’s connection to animals such as the otter and her probable role as a protector of aquatic life hints at this possible blending of traditions. Artemis’s role as a guardian of all wild creatures, both land and water, reinforces the idea that the Dacians may have seen in Vidra a similar protector of the natural world.

The Role of Women and Water Deities in Dacian Religion

Women in Dacian society played a significant role in religious ceremonies, often centered around elements like water and earth. Hadrian Daicoviciu, in Dacii, notes that "Femeile jucau un rol important în ceremoniile religioase dacice, adesea legate de elementele naturii precum pământul și apa." ("Women played an important role in Dacian religious ceremonies, often connected to elements of nature such as earth and water.") The reverence for water, coupled with Vidra’s symbolic association with the otter, suggests that she could have been invoked in fertility rites and purification ceremonies, ensuring the well-being of the community.

Archaeological evidence supports this connection to water, as many Dacian and Thracian settlements were located near rivers and lakes. Ion Horațiu Crișan’s Spiritualitatea geto-dacilor emphasizes this point: "Deși cunoștințele noastre despre zeii dacilor sunt limitate, cultul apelor și a râurilor este confirmat de numeroase descoperiri arheologice în apropierea surselor de apă." ("Although our knowledge of the Dacian gods is limited, the cult of waters and rivers is confirmed by numerous archaeological finds near water sources.") While Vidra may not have a well-documented pantheon, her symbolic presence as a water goddess fits into this broader understanding of Dacian spiritual life.

Vidra in the Neolithic and Eneolithic Context

Vidra’s origins may stretch back even further, to the Neo-Eneolithic period, a time that marked the beginning of human settlements and the development of material and spiritual culture in the region. The Neolithic Age, also called the Neo-Eneolithic, was divided into four stages:

Early Neolithic (around 6100-5500 B.C.)

Development of the Neolithic period (around 5500-5000 B.C.)

Early Eneolithic (around 5000-4500 B.C.)

Development of the Eneolithic period (around 4500-3800 B.C.)

It was during this period that human settlements began to flourish around rivers and fertile lands. In Bucharest, Neo-Eneolithic vestiges were discovered after 1920, when Vasile Pârvan founded the Bucharest Archaeological Site. Discoveries along the Colentina and Dâmbovița rivers revealed settlements belonging to the Dudesti and later Boian cultures, two important Neolithic communities in the area. These discoveries not only shed light on the early inhabitants of Bucharest but also provide insight into their spiritual world, where water and river deities like Vidra would have played a significant role.

In the Eneolithic period, anthropomorphic representations began to appear, further expanding the spiritual and artistic scope of the time. Anthropomorphic vessels, such as the famous Goddess of Vida, highlighted the connection between humans and the divine, blending the physical and spiritual worlds. These representations were often found in settlements situated at Glina, Vidra, Măgura Jilava, and Chitila-Farm, all places tied to the Boian and Gumelnita cultures. The materials used to create these representations became more diverse, including clay, bone, ceramic, and even marble and gold. Such figures were symbols of protection, fertility, and the embodiment of divine feminine power.

Vidra and the Dacian Spiritual Legacy

Though the specific rituals associated with Vidra may be lost to time, it is clear that water deities played an important part in the spiritual lives of the Dacians and other ancient peoples of the region. As Vasile Pârvan notes in Getica, "Apeductele sacre și izvoarele erau considerate locuri deosebit de importante în cultul dacilor, simbolizând purificare și fertilitate." ("Sacred aqueducts and springs were considered especially important in the Dacian cult, symbolizing purification and fertility.") Rivers, springs, and the creatures living in them, such as otters, were seen as divine symbols, and Vidra’s association with these elements connects her to broader Indo-European traditions of water goddesses, such as Artemis and her Naiads.

In fact, anthropomorphic fine art from the Eneolithic period, such as the famous Zuto Brdo-Gârla Mare culture, best exemplifies this spiritual connection. Representations of divine femininity were frequently tied to solar and water cults, with ornamental motifs like concentric circles, sunbeams, spirals, and the swastika symbolizing cosmic and natural forces. Cremation, too, was often linked to solar cults, and while anthropomorphic art decreased in the Bronze Age, the Neolithic and Eneolithic periods flourished with depictions of goddesses and divine representations.

Vidra’s Legacy and Her Connection to Artemis

Vidra, as a water deity, may no longer be widely known, but her legacy lives on in the natural and spiritual symbols of Romania and the surrounding region. Her story is woven into the history of the Neolithic and Eneolithic peoples who first settled along rivers like the Colentina and Dâmbovița. The Goddess of Vida and the anthropomorphic vessels found in settlements across Bucharest attest to a deep connection between humanity and the divine forces of nature.

As modern-day archaeologists continue to uncover the ancient world of the Dacians and Thracians, the figure of Vidra reminds us of the forgotten deities who shaped the lives of early civilizations. Though her mythology may be fragmented, the echoes of her worship can still be felt in the waters and the landscapes of Romania. Vidra’s role as a possible precursor or regional counterpart to Artemis adds an intriguing dimension to our understanding of how local deities were syncretized with more dominant religious figures in the ancient world.

In Vidra, we see the potential merging of local Dacian traditions with the powerful symbolism of Artemis, creating a spiritual figure that protected the rivers, wildlife, and people who depended on them. Whether in the ancient settlements of Boian culture or the sacred rivers of Colentina and Dâmbovița, Vidra’s spirit flows on, carrying with it the legacy of the Neolithic world and the broader divine feminine traditions that spanned the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe.

Finding the Goddess Vidra

Works Cited

Crișan, Ion Horațiu. Spiritualitatea Geto-Dacilor. Editura Științifică, 1974.

Daicoviciu, Hadrian. Dacii. Editura Științifică, 1965.

Eliade, Mircea. De la Zalmoxis la Genghis-Han: Religii și Folclor din Europa Orientală. Editura Humanitas, 1995.

Pârvan, Vasile. Getica: O Protoistorie a Daciei. Editura Cultura Națională, 1926.

What a wonderful discovery, Carla! I'd never heard of goddess Vidra. Thank you so much for your wonderful write-up and the photos! Vidra appears to be headless and hollow -- like a hollow clay jar. Is that right? Her pose and shapely hips and incised decorations remind me of the seated goddess of Pazarzhik, from Bulgaria, c. 4500 B.C. (I think she is in the Natural History Museum in Vienna.) Is there any dating for Vidra more precise than Neolithic?

It has always made me wonder how much of what’s pushed forth to the surface is natural or channeled? In that we see so many politics and bureaucracy in what gets funding and what gets forgotten. And then I think too of all those places like Iraq as an example where there’s been war after war, lands destroyed and who knows what else lays buried under its grounds that will now never see the light of day because even if we do get to them, they’re probably now destroyed.

It’s as if they make things deliberately difficult for you to find, to study, and it may appear innocent like “oh it’s just politics” or lack of funding but is it really a lack of care about these things or something more sinister at play that wants to keep certain stories suppressed