Artemis in the Cyclades: A Room of Her Own

Reflections from the Museum of Cycladic Art, May 2025

Just days before Artemis’ sacred birthday on May 6th, I found myself standing in a room entirely dedicated to her at the Kykladitisses: Untold Stories of Women in the Cyclades exhibition in Athens. It was the final week, and the timing felt like a quiet invocation.

This section of the exhibition, titled Goddesses of the Islands, traced the evolving presence of female divinity across Cycladic time. It began with Neolithic and Early Cycladic figures, voluptuous forms and folded-arm marble idols often interpreted as fertility icons or Mother-Goddesses, and moved forward to the fierce and graceful figure of Artemis herself. As the exhibit suggested, the Great Goddess of earlier periods gradually evolved into figures like the Potnia Theron, Mistress of Animals, and finally, into Artemis, goddess of the wild, of girls in transition, and of sacred thresholds.

Artemis, in this vision, inherited and absorbed the powers of earlier nature deities, goddesses of rivers and springs, of fertility and guardianship. In the Cycladic world, she wasn’t alone: other powerful female deities were worshipped too, Demeter on Paros and Tenos, Cybele from Asia Minor, even Hera on Delos, placed high above Artemis and Apollo’s sanctuaries as if keeping watch. But in this room, Artemis was the centre. Six remarkable pieces brought her presence into full, varied form, statues, fragments, and reliefs that revealed her cult across islands and centuries.

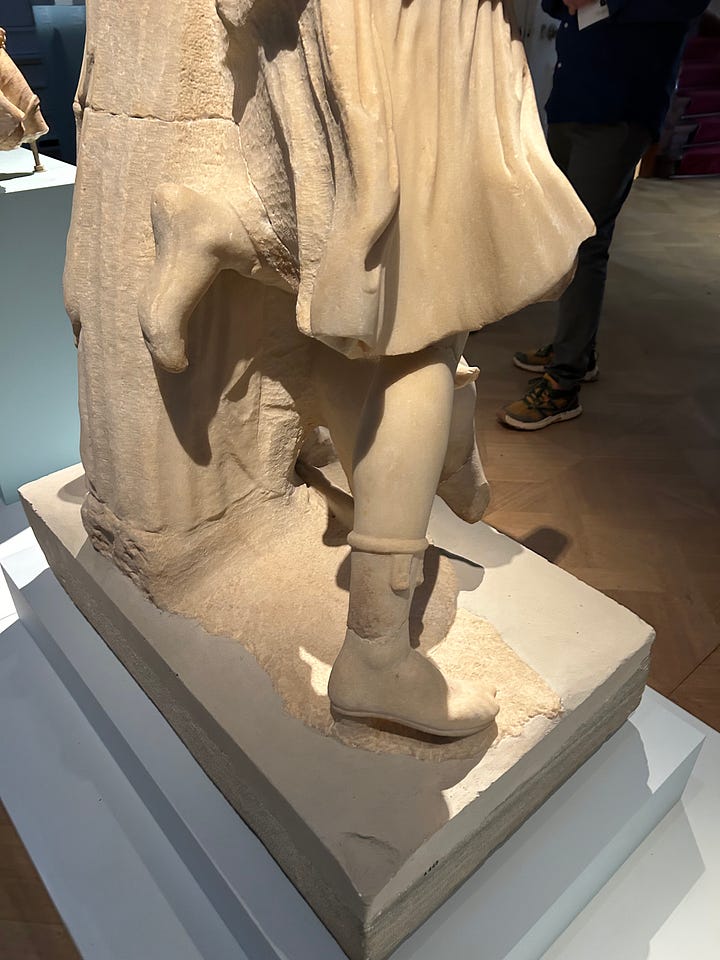

Artemis Elaphebolos – The Deer-Slayer (2nd–1st c. BCE)

From the Kykladitisses exhibition, this statue of Artemis Elaphebolos, the "Deer-Slayer," offers a rare and intimate glimpse of the goddess in one of her most ancient and wild aspects. On display for the first time outside of Delos, this late Hellenistic sculpture portrays Artemis not just as the familiar huntress, but as a fierce protector of the wild, a liminal goddess who straddled the worlds of nature, divinity, and the feminine.

The epithet Elaphebolos (from elaphos, deer, and bolos, thrower or slayer) emphasizes Artemis’s role as a powerful huntress, often invoked for successful hunts, protection of wild animals, and transition rites for young women. Her mythology reaches back to the Homeric Hymns, where she is described as “delighting in arrows” and “roaming the mountains” (Homeric Hymn to Artemis, lines 1–4). On Delos, where her cult was especially strong, the Delia festival was held in her and Apollo’s honour, featuring athletic contests, music, and dedications. This statue is not only a rare survival of that cultic context, but also a powerful reminder of the goddess's enduring wildness.

Marble Statue of Artemis Delia (4th c. BCE)

From the Sanctuary of Delian Apollo (Delion) in Paros, this Classical-period statue was an offering by a devotee named Areis. Carved from fine local marble, Artemis stands draped in a flowing chiton, her pose modest but poised. Her epithet "Delia" links her to Delos, her mythic birthplace, but also signals the rich devotional life she commanded on Paros itself. Artemis was central to Parian cult practice, appearing in inscriptions and dedications alongside local goddesses and in connection with rites of transition and protection. This statue, likely installed in a sanctuary overlooking the sea, would have served both as an offering and a symbolic embodiment of Artemis's protective and watchful presence.

Marble Statue of Artemis (ca. 120–100 BCE)

Discovered in the Theatre Quarter of Delos, this Late Hellenistic statue captures Artemis in a dynamic and elegant pose. While her arms and some features are missing, her stance conveys movement and divine poise. As Pausanias noted centuries later, “Delos was especially sacred to Artemis and Apollo, for there they were born” (Description of Greece 3.23.2). This statue may have stood in a public garden, atrium, or sanctuary, its presence a reminder of Artemis’s central role in daily life. Theatres, with their ties to Dionysus, might seem odd companions to Artemis’s wilderness, but here the divine intertwines, Artemis as a boundary-crosser, seen and invoked wherever humans dwelled and gathered.

Marble Torso of Artemis (2nd c. CE)

From Palaiopolis, Andros, this Roman-era torso is powerful even in its fragmentation. The goddess twists slightly, draped in windswept garments that cling to her form in motion. Her quiver still rests on her back, secured by a baldric, marking her as the ever-ready huntress. Artemis’s cult on Andros is less well-documented than in Delos or Paros, but archaeological evidence, including this torso, suggests her worship remained vibrant during the Imperial era. She persisted not as an abstract symbol, but as a living, protectress force integrated into both civic and rural identity.

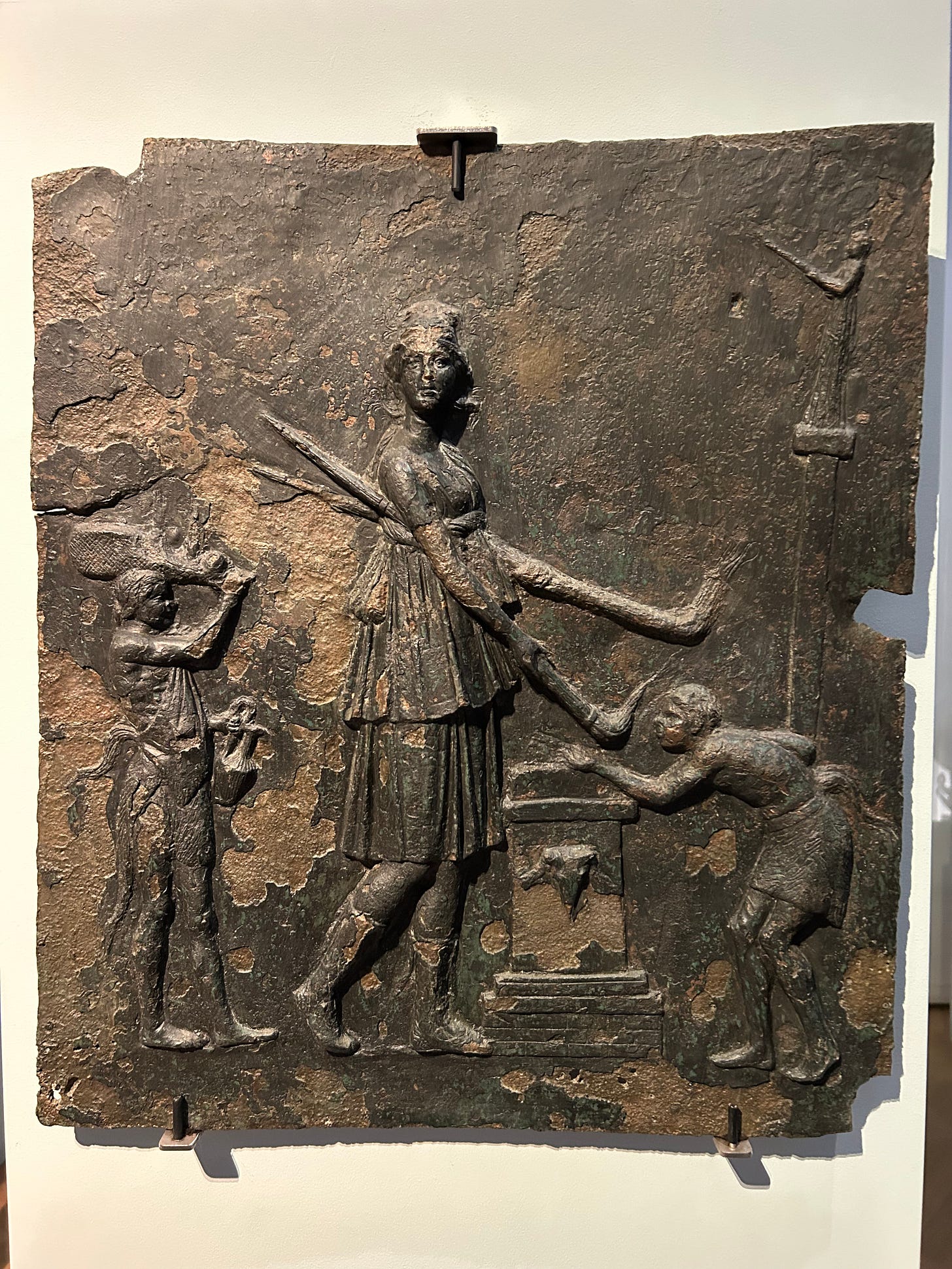

Bronze Relief with Artemis (late 3rd – early 2nd c. BCE)

This bronze relief, found at the so-called Minoan Fountain on Delos, depicts Artemis holding torches and participating in a ritual scene that includes satyrs, a detail that immediately invites interpretation. The term “Minoan” in this context likely reflects architectural style or a perceived connection to earlier cultic layers on Delos, rather than a direct link to Minoan civilization. The iconography is rich: Artemis with torches is a motif associated with her role in nocturnal rites and liminal transitions, and her presence alongside satyrs, traditionally companions of Dionysus, suggests a syncretic blending of ritual contexts. Rather than contradicting her identity, the presence of satyrs may reinforce her dominion over threshold spaces, where the wild and the sacred intersect. This relief does not merely depict a myth, it gestures toward actual ritual practice, embedding Artemis in a shared ceremonial landscape on the island.

Marble Fragment of Artemis Ephesia (1st–2nd c. CE)

This fragmentary statue of Artemis Ephesia, from the Archaeological Museum of Siphnos, represents a localized version of the goddess rooted in Anatolian tradition. Her columnar form and chest covered in symbolic objects, commonly misinterpreted as multiple breasts, represent fertility, bees, and ritual offerings. The cult statue in Ephesus, described by Pliny the Elder (Natural History 16.79), was already ancient in his time, said to be made of wood and housed in a temple known for its grandeur and mystique. The inclusion of this Ephesian form in a Cycladic exhibition speaks to the expansive and cross-cultural nature of Artemis worship. Even on a smaller island like Siphnos, Artemis Ephesia’s influence could be felt, adapted into local religious life and re-contextualized within the sacred landscape of the Aegean.

To see these six pieces together, to walk from one form of Artemis to another, to trace her worship across centuries and across islands, was an extraordinary experience. These were not just statues. They were stories, rites, songs, invocations. They were the physical remains of a living tradition.

And it meant something that I saw them all just before her birthday.

She is the huntress, the protector, the torchbearer, the guardian of transitions. And for a few shining weeks, in a quiet room in Athens, she was gathered back to herself.

It was a room of her own. And I was lucky to be in it.

Ready to dive deeper into the world of ancient goddesses and transformative knowledge? Join me on an unforgettable journey through online courses on the Artemis Centre Learning Platform, exclusive YouTube content with The Goddess Project, and immerse yourself in the mythology of the Greek Artemis with my book She Who Hunts. Whether you're looking to learn, explore, or simply get inspired, there’s something for every curious soul. Take the next step in your goddess adventure—your path to wisdom and empowerment starts here!

References

Homeric Hymn to Artemis. Translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. In Homeric Hymns and Homerica, Loeb Classical Library No. 57. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914.

Pausanias. Description of Greece, 3.23.2. Translated by W.H.S. Jones and H.A. Ormerod. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1918.

Pliny the Elder. Natural History, 16.79. Translated by H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938.

Exhibition Reference

Kykladitisses: Untold Stories of Women in the Cyclades. Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens. Curated exhibition text from the section “Goddesses of the Islands.” Exhibition closed May 4, 2025. Museum of Cycladic Art